1. Why this topic

Today, Indians and India are frequently criticized online — by outsiders and by Indians themselves. The criticism is strikingly consistent.

For example, people point to:

- Weak civic sense in public spaces

- Hyper-competitive, zero-sum behavior

- Short-term thinking and low trust

- High anxiety despite formal education

- Limited long-term value creation

At the same time, there is a deep contradiction.

On one hand, India has expanded education aggressively. On the other hand, the outcomes remain disappointing:

- Syllabi keep growing every year

- Degrees are more common than ever

- Educated unemployment remains high

- Public behavior problems continue

- Social anxiety appears to be rising

Whenever a new concern emerges, the response is predictable.

“Add it to the syllabus.”

As a result, civic sense, ethics, environment, financial literacy, and mental health are all pushed into textbooks. However, this approach has not solved the underlying problems.

Instead, it has produced new ones.

First, learning becomes overloaded and mechanical. Second, teachers turn into delivery agents rather than mentors. Third, students optimize for exams instead of becoming responsible citizens.

Therefore, we must face an uncomfortable conclusion:

Education, as currently structured, is not producing the kind of individuals or public behavior India needs.

This does not mean education is unimportant. Rather, it means we are asking it to do the wrong job, in the wrong way, using the wrong tools.

For this reason, a different approach is needed.

2. Why earlier HRD in government didn’t work — and what must change

India already experimented with Human Resource Development through the Ministry of HRD between 1985 and 2020. Yet, civic behavior, trust, and long-term thinking did not improve.

The reason was not a lack of intent. Instead, it was a failure of design.

Why the old HRD failed

To begin with, HRD was interpreted as manpower planning, not human development. As a result, people were treated as economic inputs rather than behavioral beings.

Moreover, the system rushed into quantitative KPIs before understanding how humans actually behave. Because bureaucracy prefers numbers, HRD slowly became about seats, cut-offs, and enrollments.

Consequently, values, habits, and psychology were sidelined.

In short:

India tried to measure humans before understanding them.

This inversion created predictable outcomes:

- Credential inflation without real capability

- Exam-centric systems that killed curiosity

- Compliance replacing conscience

- Rule expansion alongside behavioral decline

The key lesson

In contrast, private-sector HR evolved differently.

First, organizations define desired behaviors and culture. Next, they design systems and environments to support those behaviors. Only then do they measure outcomes.

Government HRD did the opposite.

The new approach in brief

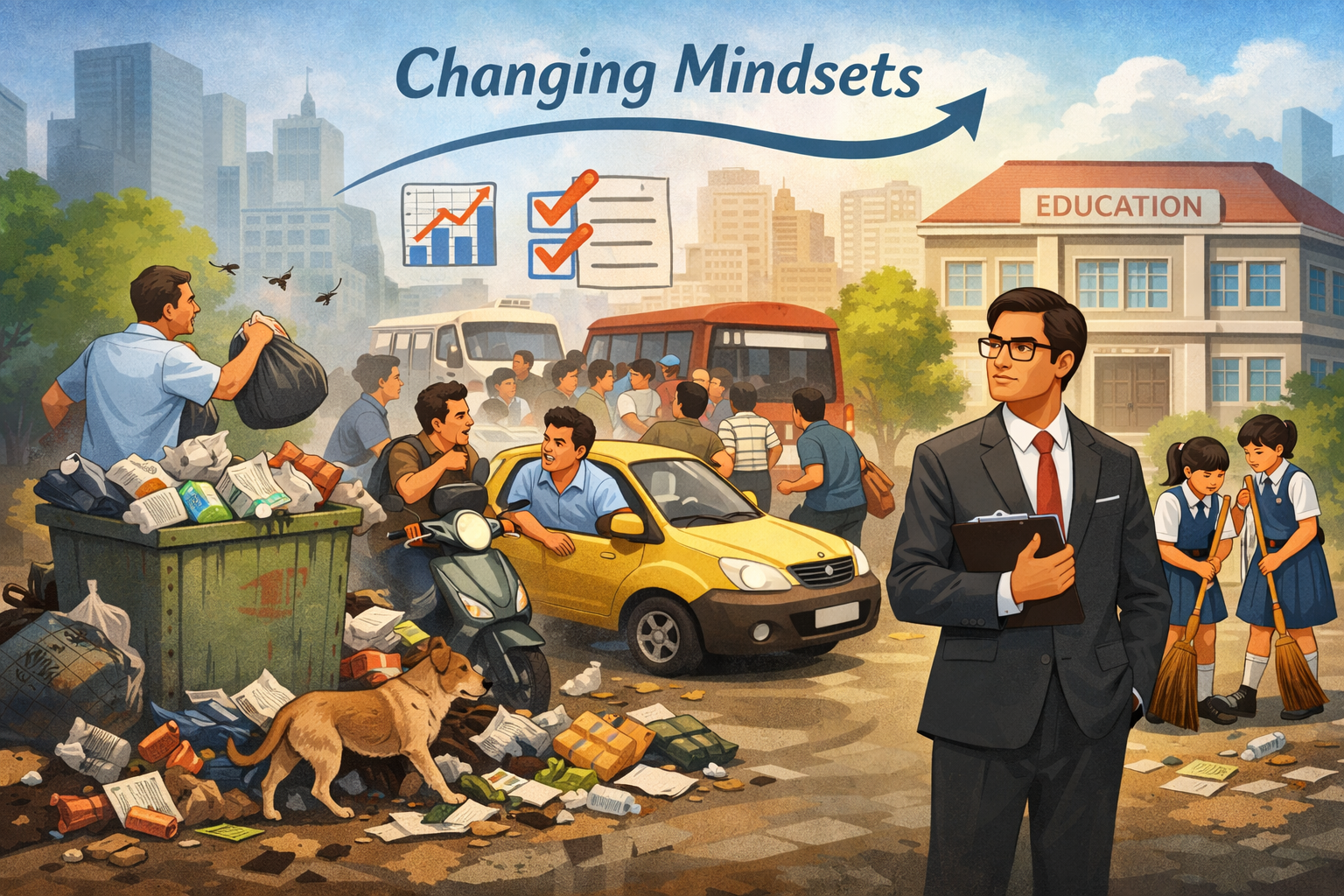

The HRD proposed here is not a line ministry and not a syllabus-writing authority. Instead, it is a meta-governance function that:

- Defines ideal behaviors for citizens and state actors

- Audits whether government systems enable those behaviors

- Uses public sentiment as feedback

- Avoids coercion, moral policing, and KPI obsession

In effect, it functions like a real HR and organizational design unit.

3. The proposal: A modern HRD for governance

3.1 HRD defines behavioral intent, not rules

The first responsibility of HRD is to define behavioral intent. It does not issue laws, punishments, or performance targets.

Instead, it publishes personas and scenarios across three domains:

- Individual behavior in public spaces

- Group behavior in shared settings

- State actor behavior in positions of authority

These descriptions are descriptive, not coercive. They resemble corporate leadership principles rather than legal commands.

3.2 HRD as the source of intent for governance

Once intent is clear, every ministry must map its major rules and policies to these personas.

Accordingly, each policy should answer three questions:

- Which behavior is this trying to encourage?

- Which persona does it assume?

- What unintended behavior might it create?

This creates traceability:

Intent → Rule → Behavior → Outcome → Public perception

Currently, governance stops at rule issuance. This framework extends responsibility to real-world effects.

3.3 HR audit: detecting contradictions, not enforcing compliance

Under this model, HR audit has limited power by design.

It does not punish or grade officials. Instead, it highlights behavioral contradictions.

For instance, it flags rules that:

- Require unrealistic human discipline

- Normalize visual disorder

- Depend excessively on enforcement

By doing so, it shifts the focus from blame to system design.

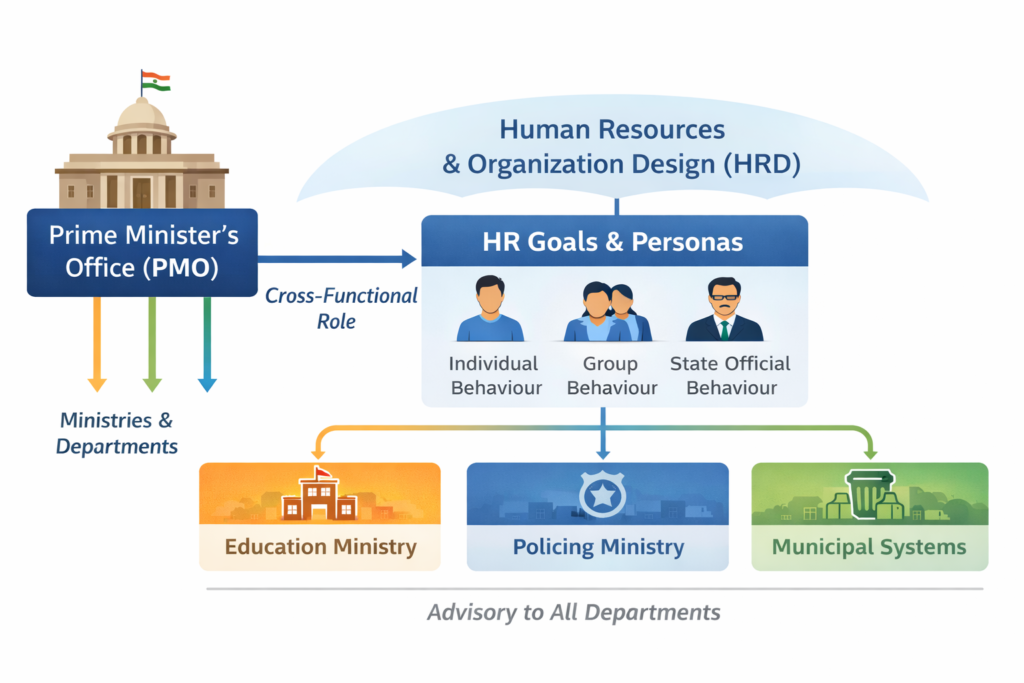

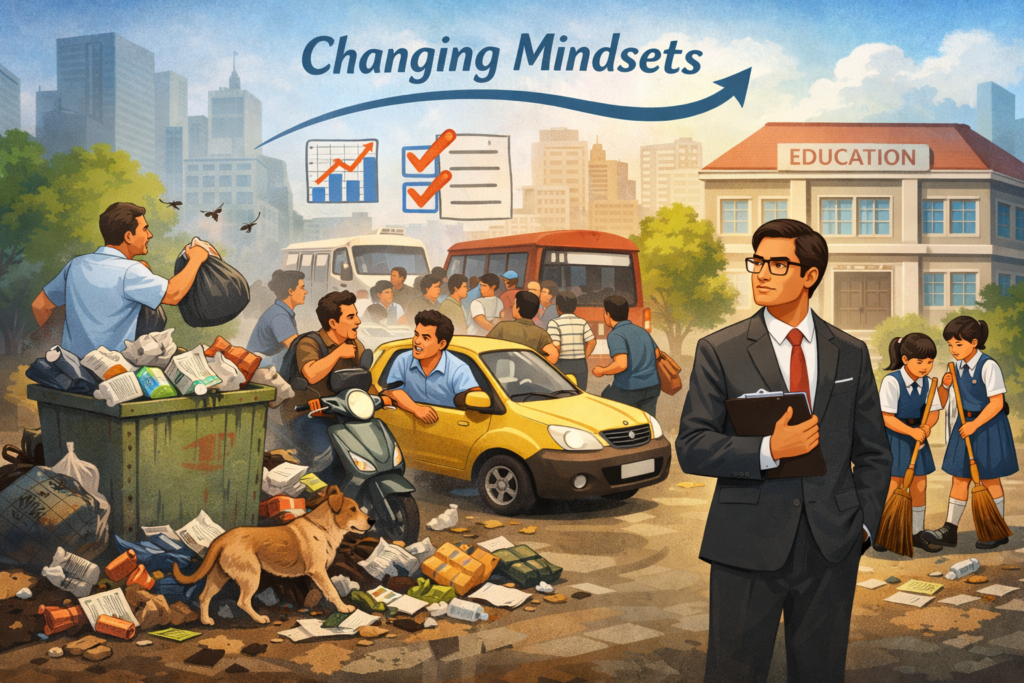

3.4 A concrete example: Waste management and behavior

Waste management clearly shows how well-intended rules can damage behavior.

The stated intent is simple: clean streets and responsible citizens.

However, common designs rely on door-to-door collection while removing public bins. This assumes perfect household compliance.

In reality, missed collections lead to discreet dumping. Over time, visible waste becomes normal. As a result, both residents and tourists internalize decay as expected.

Therefore, the system does not merely fail. It actively trains bad habits.

Under the proposed HRD framework, this would be flagged as a contradiction between intent and outcome. The response would not be punishment, but redesign.

Possible directions include hybrid bin models, better visual cues, and schedules aligned with real routines.

Ultimately, this is not a sanitation problem. It is a human systems design problem.

3.5 Education ministry’s role — especially primary education

Primary education is where this framework becomes most effective.

HRD does not write textbooks. Instead, it reviews whether curriculum delivery helps children practice the desired personas.

This shifts attention from content to daily routines.

For example, do children manage shared spaces? Do they practice cooperation and disagreement? Is authority reasoned rather than arbitrary?

Because habits form early, these experiences matter more than additional chapters.

3.6 Feedback through public sentiment, not bureaucratic metrics

Finally, feedback comes from public sentiment rather than dashboards.

Media narratives, social discourse, and citizen trust provide signals that are hard to fake and easy to contest.

Importantly, sentiment is never tied to punishment. Instead, it informs reflection and redesign.

4. Why this approach is different

This model treats governance as organizational design rather than rule production.

It recognizes that systems train behavior, whether intentionally or not. Therefore, it restores education to habit formation and limits metric obsession.

5. Closing thought

India’s problem is not a lack of intelligence or ambition.

Rather, we designed systems that reward short-term optimization and then blamed citizens for behaving exactly as trained.

A modern HRD does not moralize. Instead, it asks a harder question:

What kind of people are our systems quietly producing every day?